Wave–particle Duality on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Wave–particle duality is the concept in

Electrons from the source hit a wall with two thin slits. A mask behind the slits can expose either one or open to expose both slits. The results for high electron intensity are shown on the right, first for each slit individually, then with both slits open. With either slit open there is a smooth intensity variation due to diffraction. When both slits are open the intensity oscillates, characteristic of wave interference.

Having observed wave behavior, now change the experiment, lowering the intensity of the electron source until only one or two are detected per second, appearing as individual particles, dots in the video. As shown in the movie clip below, the dots on the detector seem at first to be random. After some time a pattern emerges, eventually forming an alternating sequence of light and dark bands.

The experiment shows wave interference revealed a single particle at a time—quantum mechanical electrons display both wave and particle behavior. Similar results have been shown for atoms and even large molecules.

Electrons from the source hit a wall with two thin slits. A mask behind the slits can expose either one or open to expose both slits. The results for high electron intensity are shown on the right, first for each slit individually, then with both slits open. With either slit open there is a smooth intensity variation due to diffraction. When both slits are open the intensity oscillates, characteristic of wave interference.

Having observed wave behavior, now change the experiment, lowering the intensity of the electron source until only one or two are detected per second, appearing as individual particles, dots in the video. As shown in the movie clip below, the dots on the detector seem at first to be random. After some time a pattern emerges, eventually forming an alternating sequence of light and dark bands.

The experiment shows wave interference revealed a single particle at a time—quantum mechanical electrons display both wave and particle behavior. Similar results have been shown for atoms and even large molecules.

While electrons were thought to be particles until their wave properties were discovered, for photons it was the opposite. In 1887,

While electrons were thought to be particles until their wave properties were discovered, for photons it was the opposite. In 1887,  where ''h'' is the

where ''h'' is the

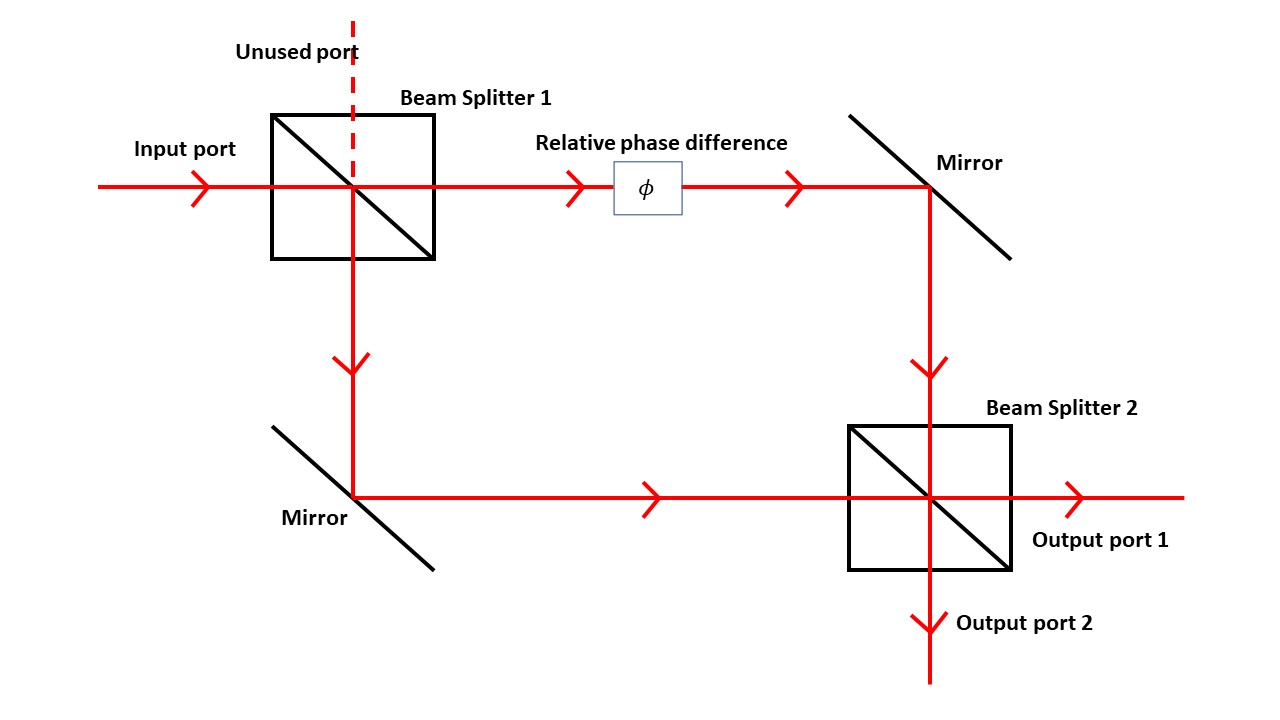

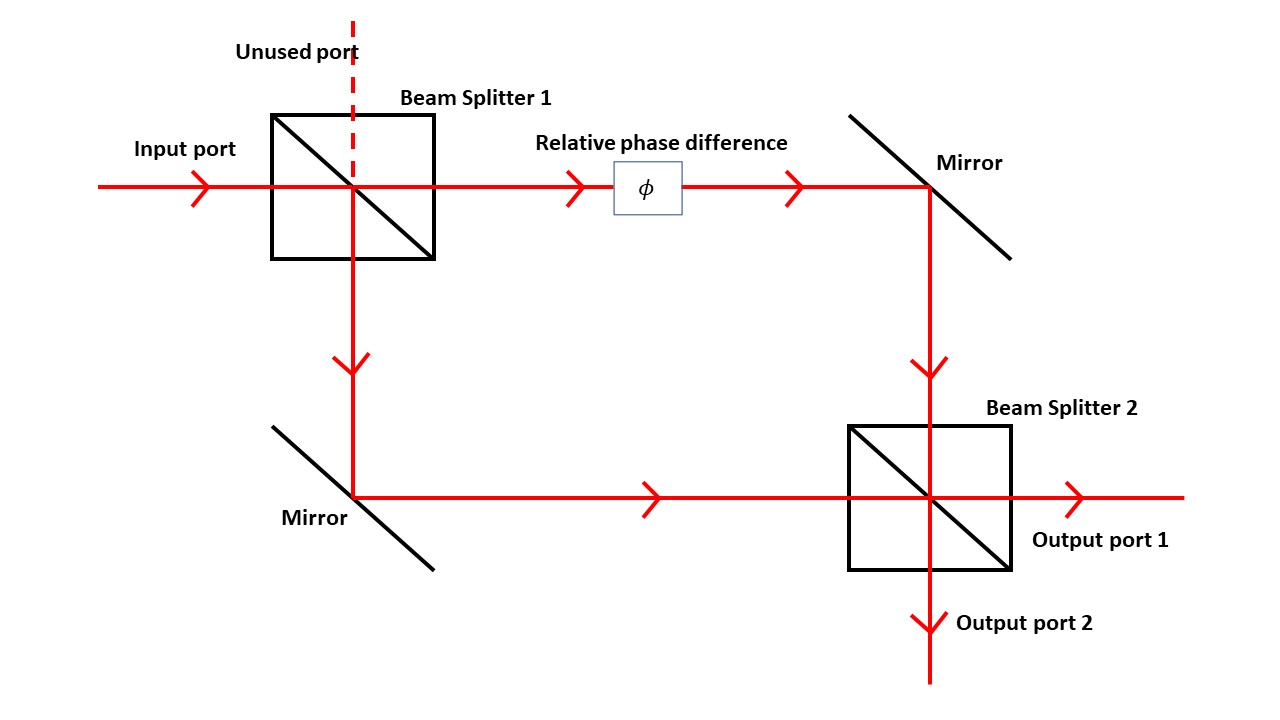

A laser beam along the input port splits at a half-silvered mirror. Part of the beam continues straight, passes though a glass phase shifter, then reflects downward. The other part of the beam reflects from the first mirror then turns at another mirror. The two beams meet at a second half-silvered beam splitter.

Each output port has a camera to record the results. The two beams show interference characteristic of wave propagation. If the laser intensity is turned sufficiently low, individual dots appear on the cameras, building up the pattern as in the electron example.

The first beam-splitter mirror acts like double slits, but in the interferometer case we can remove the second beam splitter. Then the beam heading down ends up in output port 1: any photon particles on this path gets counted in that port. The beam going across the top ends up on output port 2. In either case the counts will track the photon trajectories. However, as soon as the second beam splitter is removed the interference pattern disappears.

A laser beam along the input port splits at a half-silvered mirror. Part of the beam continues straight, passes though a glass phase shifter, then reflects downward. The other part of the beam reflects from the first mirror then turns at another mirror. The two beams meet at a second half-silvered beam splitter.

Each output port has a camera to record the results. The two beams show interference characteristic of wave propagation. If the laser intensity is turned sufficiently low, individual dots appear on the cameras, building up the pattern as in the electron example.

The first beam-splitter mirror acts like double slits, but in the interferometer case we can remove the second beam splitter. Then the beam heading down ends up in output port 1: any photon particles on this path gets counted in that port. The beam going across the top ends up on output port 2. In either case the counts will track the photon trajectories. However, as soon as the second beam splitter is removed the interference pattern disappears.

quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics is the fundamental physical Scientific theory, theory that describes the behavior of matter and of light; its unusual characteristics typically occur at and below the scale of atoms. Reprinted, Addison-Wesley, 1989, It is ...

that fundamental entities of the universe, like photon

A photon () is an elementary particle that is a quantum of the electromagnetic field, including electromagnetic radiation such as light and radio waves, and the force carrier for the electromagnetic force. Photons are massless particles that can ...

s and electron

The electron (, or in nuclear reactions) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary charge, elementary electric charge. It is a fundamental particle that comprises the ordinary matter that makes up the universe, along with up qua ...

s, exhibit particle

In the physical sciences, a particle (or corpuscle in older texts) is a small localized object which can be described by several physical or chemical properties, such as volume, density, or mass.

They vary greatly in size or quantity, from s ...

or wave

In physics, mathematics, engineering, and related fields, a wave is a propagating dynamic disturbance (change from List of types of equilibrium, equilibrium) of one or more quantities. ''Periodic waves'' oscillate repeatedly about an equilibrium ...

properties according to the experimental circumstances. It expresses the inability of the classical concepts such as particle or wave to fully describe the behavior of quantum objects. During the 19th and early 20th centuries, light

Light, visible light, or visible radiation is electromagnetic radiation that can be visual perception, perceived by the human eye. Visible light spans the visible spectrum and is usually defined as having wavelengths in the range of 400– ...

was found to behave as a wave then later was discovered to have a particle-like behavior, whereas electrons behaved like particles in early experiments then were later discovered to have wave-like behavior. The concept of duality arose to name these seeming contradictions.

History

Wave-particle duality of light

In the late 17th century, SirIsaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton () was an English polymath active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author. Newton was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment that followed ...

had advocated that light was corpuscular (particulate), but Christiaan Huygens

Christiaan Huygens, Halen, Lord of Zeelhem, ( , ; ; also spelled Huyghens; ; 14 April 1629 – 8 July 1695) was a Dutch mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor who is regarded as a key figure in the Scientific Revolution ...

took an opposing wave description. While Newton had favored a particle approach, he was the first to attempt to reconcile both wave and particle theories of light, and the only one in his time to consider both, thereby anticipating modern wave-particle duality. Thomas Young's interference experiments in 1801, and François Arago

Dominique François Jean Arago (), known simply as François Arago (; Catalan: , ; 26 February 17862 October 1853), was a French mathematician, physicist, astronomer, freemason, supporter of the Carbonari revolutionaries and politician.

Early l ...

's detection of the Poisson spot in 1819, validated Huygens' wave models. However, the wave model was challenged in 1901 by Planck's law for black-body radiation

Black-body radiation is the thermal radiation, thermal electromagnetic radiation within, or surrounding, a body in thermodynamic equilibrium with its environment, emitted by a black body (an idealized opaque, non-reflective body). It has a specific ...

. Max Planck

Max Karl Ernst Ludwig Planck (; ; 23 April 1858 – 4 October 1947) was a German Theoretical physics, theoretical physicist whose discovery of energy quantum, quanta won him the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1918.

Planck made many substantial con ...

heuristically derived a formula for the observed spectrum by assuming that a hypothetical electrically charged oscillator in a cavity that contained black-body radiation could only change its energy

Energy () is the physical quantity, quantitative physical property, property that is transferred to a physical body, body or to a physical system, recognizable in the performance of Work (thermodynamics), work and in the form of heat and l ...

in a minimal increment, ''E'', that was proportional to the frequency of its associated electromagnetic wave

In physics, electromagnetic radiation (EMR) is a self-propagating wave of the electromagnetic field that carries momentum and radiant energy through space. It encompasses a broad spectrum, classified by frequency or its inverse, wavelength, ...

. In 1905 Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein (14 March 187918 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist who is best known for developing the theory of relativity. Einstein also made important contributions to quantum mechanics. His mass–energy equivalence f ...

interpreted the photoelectric effect

The photoelectric effect is the emission of electrons from a material caused by electromagnetic radiation such as ultraviolet light. Electrons emitted in this manner are called photoelectrons. The phenomenon is studied in condensed matter physi ...

also with discrete energies for photons. These both indicate particle behavior. Despite confirmation by various experimental observations, the photon

A photon () is an elementary particle that is a quantum of the electromagnetic field, including electromagnetic radiation such as light and radio waves, and the force carrier for the electromagnetic force. Photons are massless particles that can ...

theory (as it came to be called) remained controversial until Arthur Compton

Arthur Holly Compton (September 10, 1892 – March 15, 1962) was an American particle physicist who won the 1927 Nobel Prize in Physics for his discovery of the Compton effect, which demonstrated the particle nature of electromagnetic radiati ...

performed a series of experiments from 1922 to 1924 demonstrating the momentum of light. The experimental evidence of particle-like momentum and energy seemingly contradicted the earlier work demonstrating wave-like interference of light.

Wave-particle duality of matter

The contradictory evidence from electrons arrived in the opposite order. Many experiments by J. J. Thomson, Robert Millikan, and Charles Wilson among others had shown that free electrons had particle properties, for instance, the measurement of their mass by Thomson in 1897. In 1924, Louis de Broglie introduced his theory ofelectron

The electron (, or in nuclear reactions) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary charge, elementary electric charge. It is a fundamental particle that comprises the ordinary matter that makes up the universe, along with up qua ...

waves in his PhD thesis ''Recherches sur la théorie des quanta''. He suggested that an electron around a nucleus could be thought of as being a standing wave

In physics, a standing wave, also known as a stationary wave, is a wave that oscillates in time but whose peak amplitude profile does not move in space. The peak amplitude of the wave oscillations at any point in space is constant with respect t ...

and that electrons and all matter could be considered as waves. He merged the idea of thinking about them as particles, and of thinking of them as waves. He proposed that particles are bundles of waves ( wave packets) that move with a group velocity

The group velocity of a wave is the velocity with which the overall envelope shape of the wave's amplitudes—known as the ''modulation'' or ''envelope (waves), envelope'' of the wave—propagates through space.

For example, if a stone is thro ...

and have an effective mass. Both of these depend upon the energy, which in turn connects to the wavevector and the relativistic formulation of Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein (14 March 187918 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist who is best known for developing the theory of relativity. Einstein also made important contributions to quantum mechanics. His mass–energy equivalence f ...

a few years before.

Following de Broglie's proposal of wave–particle duality of electrons, in 1925 to 1926, Erwin Schrödinger

Erwin Rudolf Josef Alexander Schrödinger ( ; ; 12 August 1887 – 4 January 1961), sometimes written as or , was an Austrian-Irish theoretical physicist who developed fundamental results in quantum field theory, quantum theory. In particul ...

developed the wave equation of motion for electrons. This rapidly became part of what was called by Schrödinger ''undulatory mechanics'', now called the Schrödinger equation

The Schrödinger equation is a partial differential equation that governs the wave function of a non-relativistic quantum-mechanical system. Its discovery was a significant landmark in the development of quantum mechanics. It is named after E ...

and also "wave mechanics".

In 1926, Max Born

Max Born (; 11 December 1882 – 5 January 1970) was a German-British theoretical physicist who was instrumental in the development of quantum mechanics. He also made contributions to solid-state physics and optics, and supervised the work of a ...

gave a talk in an Oxford meeting about using the electron diffraction experiments to confirm the wave–particle duality of electrons. In his talk, Born cited experimental data from Clinton Davisson in 1923. It happened that Davisson also attended that talk. Davisson returned to his lab in the US to switch his experimental focus to test the wave property of electrons.

In 1927, the wave nature of electrons was empirically confirmed by two experiments. The Davisson–Germer experiment at Bell Labs measured electrons scattered from Ni metal surfaces. George Paget Thomson and Alexander Reid at Cambridge University scattered electrons through thin nickel

Nickel is a chemical element; it has symbol Ni and atomic number 28. It is a silvery-white lustrous metal with a slight golden tinge. Nickel is a hard and ductile transition metal. Pure nickel is chemically reactive, but large pieces are slo ...

films and observed concentric diffraction rings. Alexander Reid, who was Thomson's graduate student, performed the first experiments, but he died soon after in a motorcycle accident and is rarely mentioned. These experiments were rapidly followed by the first non-relativistic diffraction model for electrons by Hans Bethe based upon the Schrödinger equation

The Schrödinger equation is a partial differential equation that governs the wave function of a non-relativistic quantum-mechanical system. Its discovery was a significant landmark in the development of quantum mechanics. It is named after E ...

, which is very close to how electron diffraction is now described. Significantly, Davisson and Germer noticed that their results could not be interpreted using a Bragg's law approach as the positions were systematically different; the approach of Bethe, which includes the refraction due to the average potential, yielded more accurate results. Davisson and Thomson were awarded the Nobel Prize in 1937 for experimental verification of wave property of electrons by diffraction experiments. Similar crystal diffraction experiments were carried out by Otto Stern in the 1930s using beams of helium

Helium (from ) is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol He and atomic number 2. It is a colorless, odorless, non-toxic, inert gas, inert, monatomic gas and the first in the noble gas group in the periodic table. Its boiling point is ...

atoms and hydrogen

Hydrogen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol H and atomic number 1. It is the lightest and abundance of the chemical elements, most abundant chemical element in the universe, constituting about 75% of all baryon, normal matter ...

molecules. These experiments further verified that wave behavior is not limited to electrons and is a general property of matter on a microscopic scale.

Classical waves and particles

Before proceeding further, it is critical to introduce some definitions of waves and particles both in a classical sense and in quantum mechanics. Waves and particles are two very different models for physical systems, each with an exceptionally large range of application. Classical waves obey the wave equation; they have continuous values at many points in space that vary with time; their spatial extent can vary with time due todiffraction

Diffraction is the deviation of waves from straight-line propagation without any change in their energy due to an obstacle or through an aperture. The diffracting object or aperture effectively becomes a secondary source of the Wave propagation ...

, and they display wave interference

In physics, interference is a phenomenon in which two coherent waves are combined by adding their intensities or displacements with due consideration for their phase difference. The resultant wave may have greater amplitude (constructive in ...

. Physical systems exhibiting wave behavior and described by the mathematics of wave equations include water waves, seismic waves

A seismic wave is a mechanical wave of acoustic wave, acoustic energy that travels through the Earth or another planetary body. It can result from an earthquake (or generally, a quake (natural phenomenon), quake), types of volcanic eruptions ...

, sound waves, radio waves

Radio waves (formerly called Hertzian waves) are a type of electromagnetic radiation with the lowest frequencies and the longest wavelengths in the electromagnetic spectrum, typically with frequencies below 300 gigahertz (GHz) and wavelengths ...

, and more.

Classical particles obey classical mechanics

Classical mechanics is a Theoretical physics, physical theory describing the motion of objects such as projectiles, parts of Machine (mechanical), machinery, spacecraft, planets, stars, and galaxies. The development of classical mechanics inv ...

; they have some center of mass

In physics, the center of mass of a distribution of mass in space (sometimes referred to as the barycenter or balance point) is the unique point at any given time where the weight function, weighted relative position (vector), position of the d ...

and extent; they follow trajectories characterized by positions and velocities that vary over time; in the absence of forces their trajectories are straight lines. Stars

A star is a luminous spheroid of plasma held together by self-gravity. The nearest star to Earth is the Sun. Many other stars are visible to the naked eye at night; their immense distances from Earth make them appear as fixed points of ...

, planets

A planet is a large, rounded astronomical body that is generally required to be in orbit around a star, stellar remnant, or brown dwarf, and is not one itself. The Solar System has eight planets by the most restrictive definition of the te ...

, spacecraft

A spacecraft is a vehicle that is designed spaceflight, to fly and operate in outer space. Spacecraft are used for a variety of purposes, including Telecommunications, communications, Earth observation satellite, Earth observation, Weather s ...

, tennis balls, bullets

A bullet is a Kinetic energy weapon, kinetic projectile, a component of firearm ammunition that is Shooting, shot from a gun barrel. They are made of a variety of materials, such as copper, lead, steel, polymer, rubber and even wax; and are made ...

, sand grains: particle models work across a huge scale. Unlike waves, particles do not exhibit interference.

Some experiments on quantum systems show wave-like interference and diffraction; some experiments show particle-like collisions.

Quantum systems obey wave equations that predict particle probability distributions. These particles are associated with discrete values called quanta for properties such as spin, electric charge

Electric charge (symbol ''q'', sometimes ''Q'') is a physical property of matter that causes it to experience a force when placed in an electromagnetic field. Electric charge can be ''positive'' or ''negative''. Like charges repel each other and ...

and magnetic moment

In electromagnetism, the magnetic moment or magnetic dipole moment is the combination of strength and orientation of a magnet or other object or system that exerts a magnetic field. The magnetic dipole moment of an object determines the magnitude ...

. These particles arrive one at time, randomly, but build up a pattern. The probability that experiments will measure particles at a point in space is the square of a complex-number valued wave. Experiments can be designed to exhibit diffraction and interference of the probability amplitude. Thus statistically large numbers of the random particle appearances can display wave-like properties. Similar equations govern collective excitations called quasiparticles.

Electrons behaving as waves and particles

The electron double slit experiment is a textbook demonstration of wave-particle duality. A modern version of the experiment is shown schematically in the figure below. Electrons from the source hit a wall with two thin slits. A mask behind the slits can expose either one or open to expose both slits. The results for high electron intensity are shown on the right, first for each slit individually, then with both slits open. With either slit open there is a smooth intensity variation due to diffraction. When both slits are open the intensity oscillates, characteristic of wave interference.

Having observed wave behavior, now change the experiment, lowering the intensity of the electron source until only one or two are detected per second, appearing as individual particles, dots in the video. As shown in the movie clip below, the dots on the detector seem at first to be random. After some time a pattern emerges, eventually forming an alternating sequence of light and dark bands.

The experiment shows wave interference revealed a single particle at a time—quantum mechanical electrons display both wave and particle behavior. Similar results have been shown for atoms and even large molecules.

Electrons from the source hit a wall with two thin slits. A mask behind the slits can expose either one or open to expose both slits. The results for high electron intensity are shown on the right, first for each slit individually, then with both slits open. With either slit open there is a smooth intensity variation due to diffraction. When both slits are open the intensity oscillates, characteristic of wave interference.

Having observed wave behavior, now change the experiment, lowering the intensity of the electron source until only one or two are detected per second, appearing as individual particles, dots in the video. As shown in the movie clip below, the dots on the detector seem at first to be random. After some time a pattern emerges, eventually forming an alternating sequence of light and dark bands.

The experiment shows wave interference revealed a single particle at a time—quantum mechanical electrons display both wave and particle behavior. Similar results have been shown for atoms and even large molecules.

Observing photons as particles

Heinrich Hertz

Heinrich Rudolf Hertz (; ; 22 February 1857 – 1 January 1894) was a German physicist who first conclusively proved the existence of the electromagnetic waves predicted by James Clerk Maxwell's equations of electromagnetism.

Biography

Heinri ...

observed that when light with sufficient frequency hits a metallic surface, the surface emits cathode rays

Cathode rays are streams of electrons observed in vacuum tube, discharge tubes. If an evacuated glass tube is equipped with two electrodes and a voltage is applied, glass behind the positive electrode is observed to glow, due to electrons emitte ...

, what are now called electrons. In 1902, Philipp Lenard discovered that the maximum possible energy of an ejected electron is unrelated to its intensity. This observation is at odds with classical electromagnetism, which predicts that the electron's energy should be proportional to the intensity of the incident radiation. Alt URL. In 1905, Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein (14 March 187918 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist who is best known for developing the theory of relativity. Einstein also made important contributions to quantum mechanics. His mass–energy equivalence f ...

suggested that the energy of the light must occur a finite number of energy quanta. translated into English as The term "photon" was introduced in 1926. He postulated that electrons can receive energy from an electromagnetic field only in discrete units (quanta or photons): an amount of energy

Energy () is the physical quantity, quantitative physical property, property that is transferred to a physical body, body or to a physical system, recognizable in the performance of Work (thermodynamics), work and in the form of heat and l ...

''E'' that was related to the frequency

Frequency is the number of occurrences of a repeating event per unit of time. Frequency is an important parameter used in science and engineering to specify the rate of oscillatory and vibratory phenomena, such as mechanical vibrations, audio ...

''f'' of the light by

:

Planck constant

The Planck constant, or Planck's constant, denoted by h, is a fundamental physical constant of foundational importance in quantum mechanics: a photon's energy is equal to its frequency multiplied by the Planck constant, and the wavelength of a ...

(6.626×10−34 J⋅s). Only photons of a high enough frequency (above a certain ''threshold'' value which, when multiplied by the Planck constant, is the work function

In solid-state physics, the work function (sometimes spelled workfunction) is the minimum thermodynamic work (i.e., energy) needed to remove an electron from a solid to a point in the vacuum immediately outside the solid surface. Here "immediately" ...

) could knock an electron free. For example, photons of blue light had sufficient energy to free an electron from the metal he used, but photons of red light did not. One photon of light above the threshold frequency could release only one electron; the higher the frequency of a photon, the higher the kinetic energy of the emitted electron, but no amount of light below the threshold frequency could release an electron. Despite confirmation by various experimental observations, the photon

A photon () is an elementary particle that is a quantum of the electromagnetic field, including electromagnetic radiation such as light and radio waves, and the force carrier for the electromagnetic force. Photons are massless particles that can ...

theory (as it came to be called later) remained controversial until Arthur Compton

Arthur Holly Compton (September 10, 1892 – March 15, 1962) was an American particle physicist who won the 1927 Nobel Prize in Physics for his discovery of the Compton effect, which demonstrated the particle nature of electromagnetic radiati ...

performed a series of experiments from 1922 to 1924 demonstrating the momentum of light.

Both discrete (quantized) energies and also momentum are, classically, particle attributes. There are many other examples where photons display particle-type properties, for instance in solar sails, where sunlight could propel a space vehicle and laser cooling

Laser cooling includes several techniques where atoms, molecules, and small mechanical systems are cooled with laser light. The directed energy of lasers is often associated with heating materials, e.g. laser cutting, so it can be counterintuit ...

where the momentum is used to slow down (cool) atoms. These are a different aspect of wave-particle duality.

Which slit experiments

In a "which way" experiment, particle detectors are placed at the slits to determine which slit the electron traveled through. When these detectors are inserted, quantum mechanics predicts that the interference pattern disappears because the detected part of the electron wave has changed (loss of coherence). Many similar proposals have been made and many have been converted into experiments and tried out. Every single one shows the same result: as soon as electron trajectories are detected, interference disappears. A simple example of these "which way" experiments uses a Mach–Zehnder interferometer, a device based on lasers and mirrors sketched below. A laser beam along the input port splits at a half-silvered mirror. Part of the beam continues straight, passes though a glass phase shifter, then reflects downward. The other part of the beam reflects from the first mirror then turns at another mirror. The two beams meet at a second half-silvered beam splitter.

Each output port has a camera to record the results. The two beams show interference characteristic of wave propagation. If the laser intensity is turned sufficiently low, individual dots appear on the cameras, building up the pattern as in the electron example.

The first beam-splitter mirror acts like double slits, but in the interferometer case we can remove the second beam splitter. Then the beam heading down ends up in output port 1: any photon particles on this path gets counted in that port. The beam going across the top ends up on output port 2. In either case the counts will track the photon trajectories. However, as soon as the second beam splitter is removed the interference pattern disappears.

A laser beam along the input port splits at a half-silvered mirror. Part of the beam continues straight, passes though a glass phase shifter, then reflects downward. The other part of the beam reflects from the first mirror then turns at another mirror. The two beams meet at a second half-silvered beam splitter.

Each output port has a camera to record the results. The two beams show interference characteristic of wave propagation. If the laser intensity is turned sufficiently low, individual dots appear on the cameras, building up the pattern as in the electron example.

The first beam-splitter mirror acts like double slits, but in the interferometer case we can remove the second beam splitter. Then the beam heading down ends up in output port 1: any photon particles on this path gets counted in that port. The beam going across the top ends up on output port 2. In either case the counts will track the photon trajectories. However, as soon as the second beam splitter is removed the interference pattern disappears.

See also

* * * Einstein's thought experiments *Interpretations of quantum mechanics

An interpretation of quantum mechanics is an attempt to explain how the mathematical theory of quantum mechanics might correspond to experienced reality. Quantum mechanics has held up to rigorous and extremely precise tests in an extraordinarily b ...

*

* Uncertainty principle

The uncertainty principle, also known as Heisenberg's indeterminacy principle, is a fundamental concept in quantum mechanics. It states that there is a limit to the precision with which certain pairs of physical properties, such as position a ...

* Matter wave

* Corpuscular theory of light

References

External links

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Wave Particle Duality Articles containing video clips Dichotomies Foundational quantum physics Waves Particles